As of September 26, 2022, we have captured and conducted quality review of 20,263 images (768 GB) from twelve partner institutions: Bowling Green State University, DePauw University, Earlham College, Goshen College, Illinois Wesleyan University, Knox College, Loyola University Chicago, Muskegon Museum of Art, Northern Illinois University, Saint Mary’s College, St. Meinrad Archabbey, and Xavier University. Contributing to the digitization efforts are partners from Bowling Green and Northern Illinois who digitized their own items, while the bulk of the digitization work is happening at Indiana University Bloomington. We began digitization work in Bloomington during the summer of 2021 (delayed due to the pandemic). Now that we have been digitizing materials a little over a year, we would like to provide a behind-the-scenes look into the digitization process, which extends, on both ends, before and beyond the point of capture.

For context, our original grant application estimated 78 codices and 406 fragments across 22 partner collections. Partners diligently worked to compile an inventory of materials with basic condition assessment information. Project leads and subject experts, Liz Hebbard, Sarah Noonan and Ian Cornelius, conducted 23 site visits (St. Meinrad hosted us twice) during which the inventory was verified and updated to reflect additional materials in scope not originally reported, including another round of condition assessment. Upon conclusion of the site visits, our proposed number of manuscripts changed to 74 codices and 615 fragments. We also learned that the original folio count for codices was significantly underestimated, and although we have 4 fewer codices on the digitization list, the number of folios to be imaged has increased substantially. Our digitization costs have now increased by roughly $20,000, but that’s for another blog post. For now, we hope to move forward, redirecting funds originally slotted for several in-person meetings that were thwarted by the pandemic.

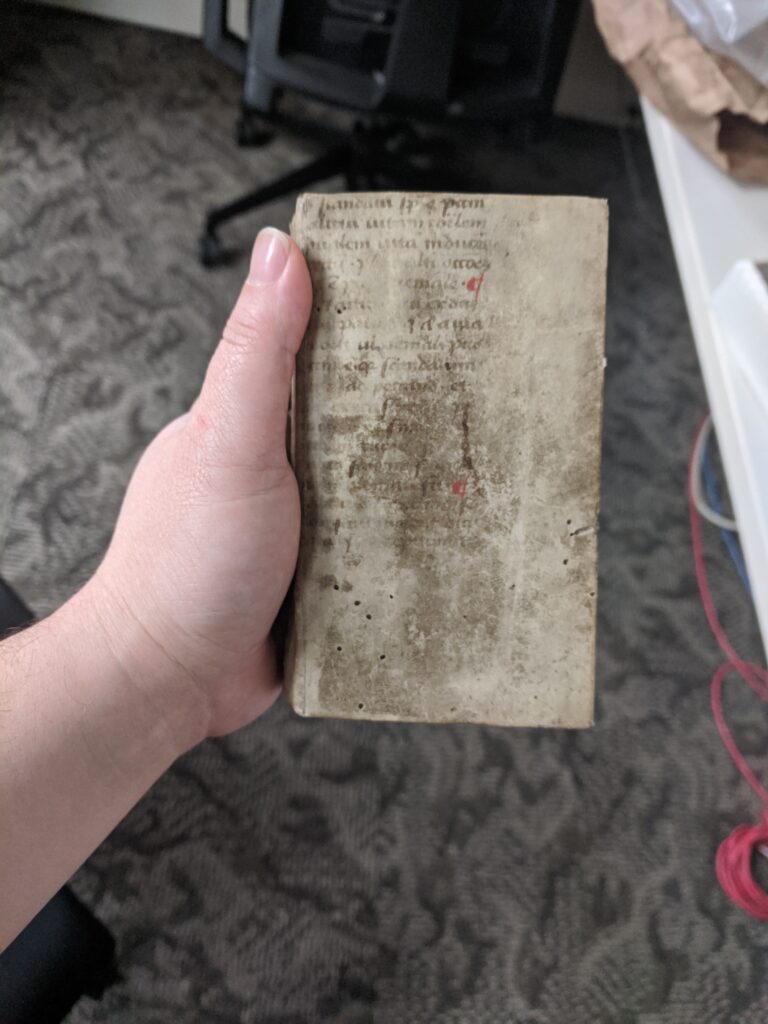

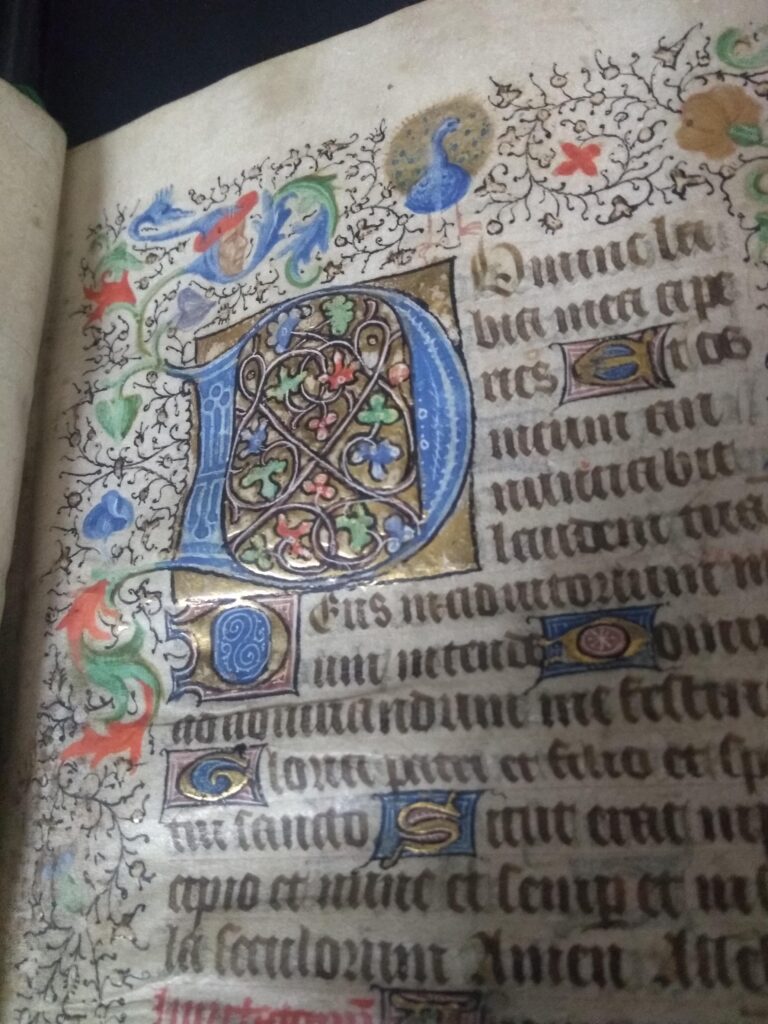

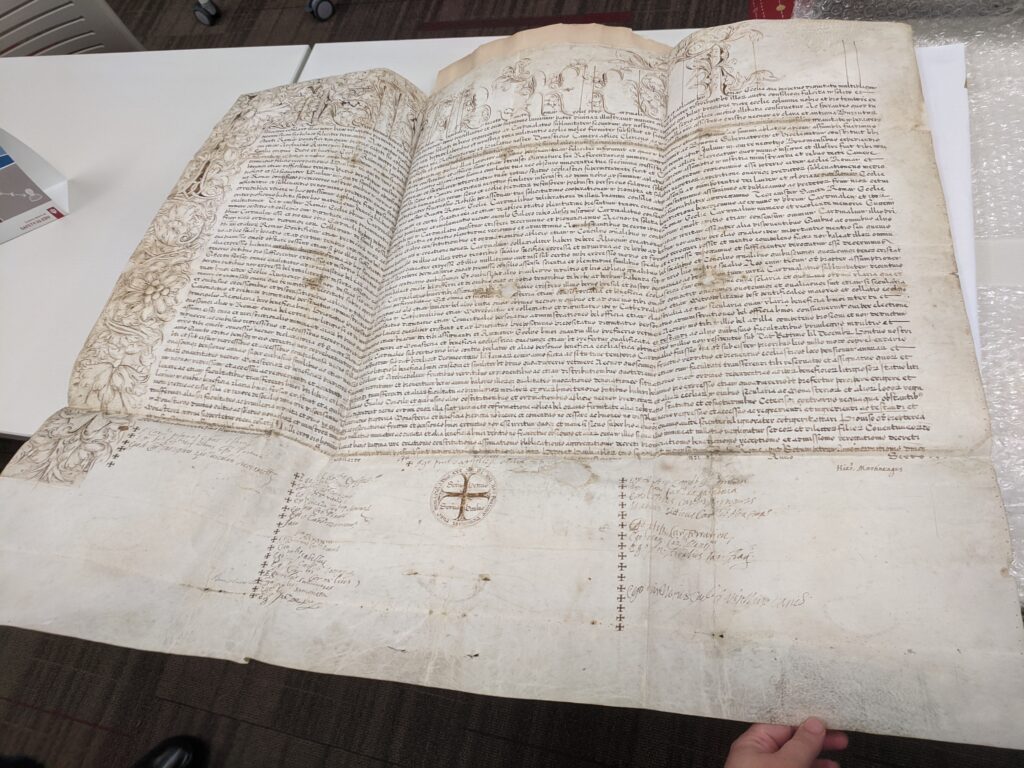

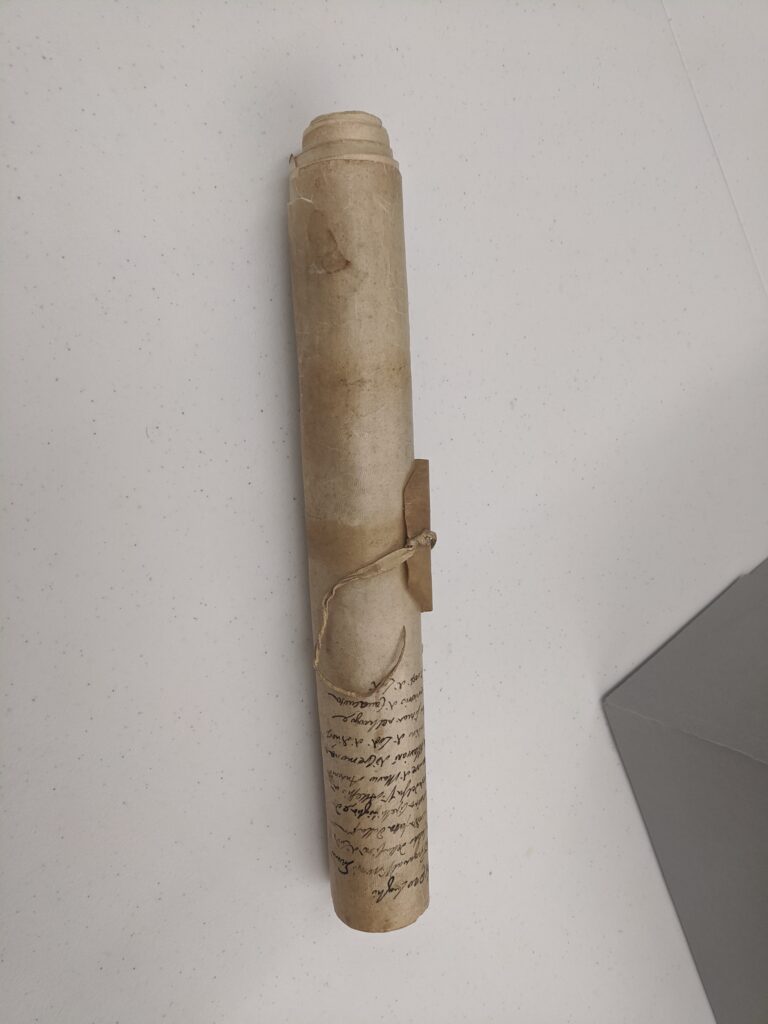

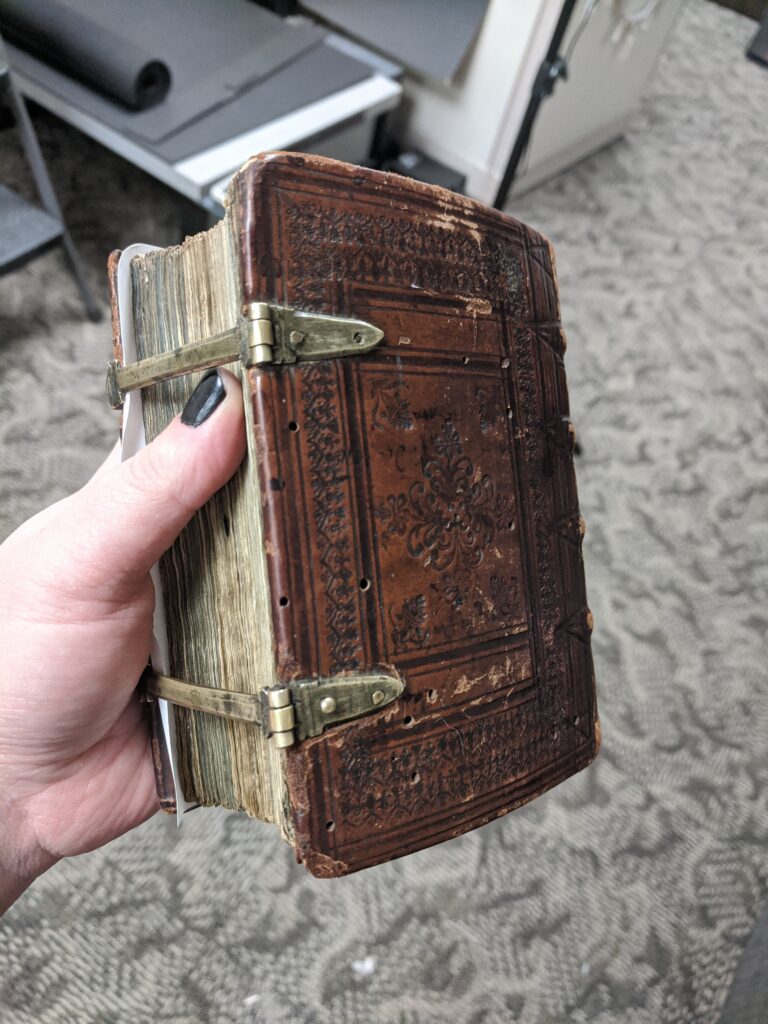

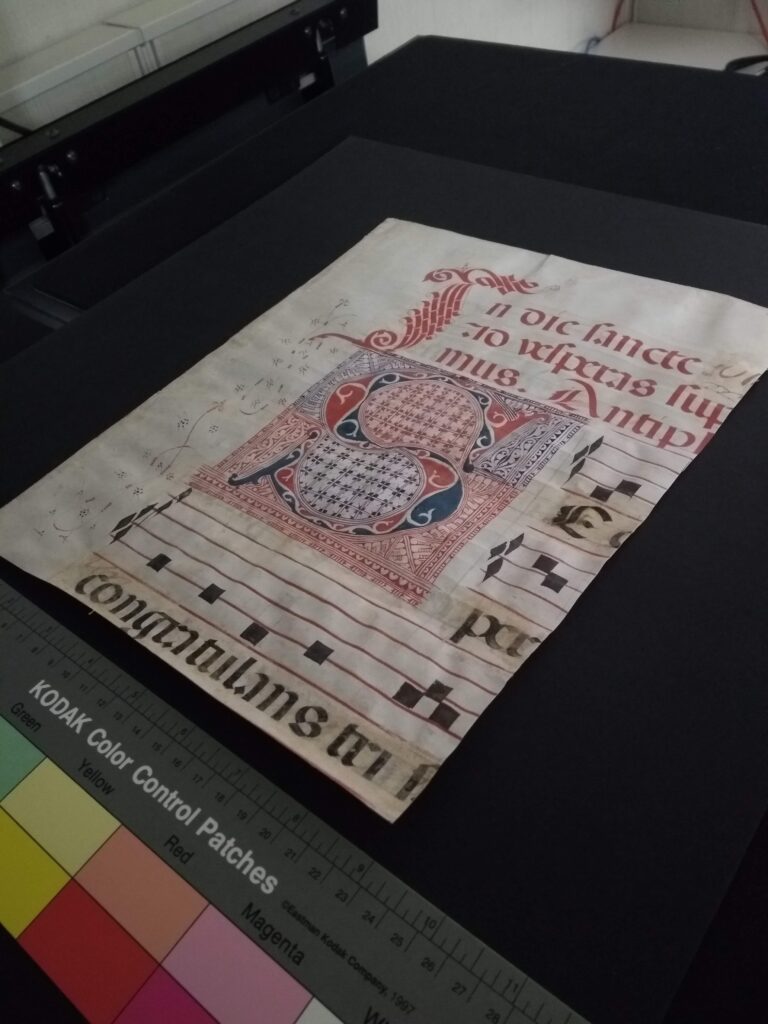

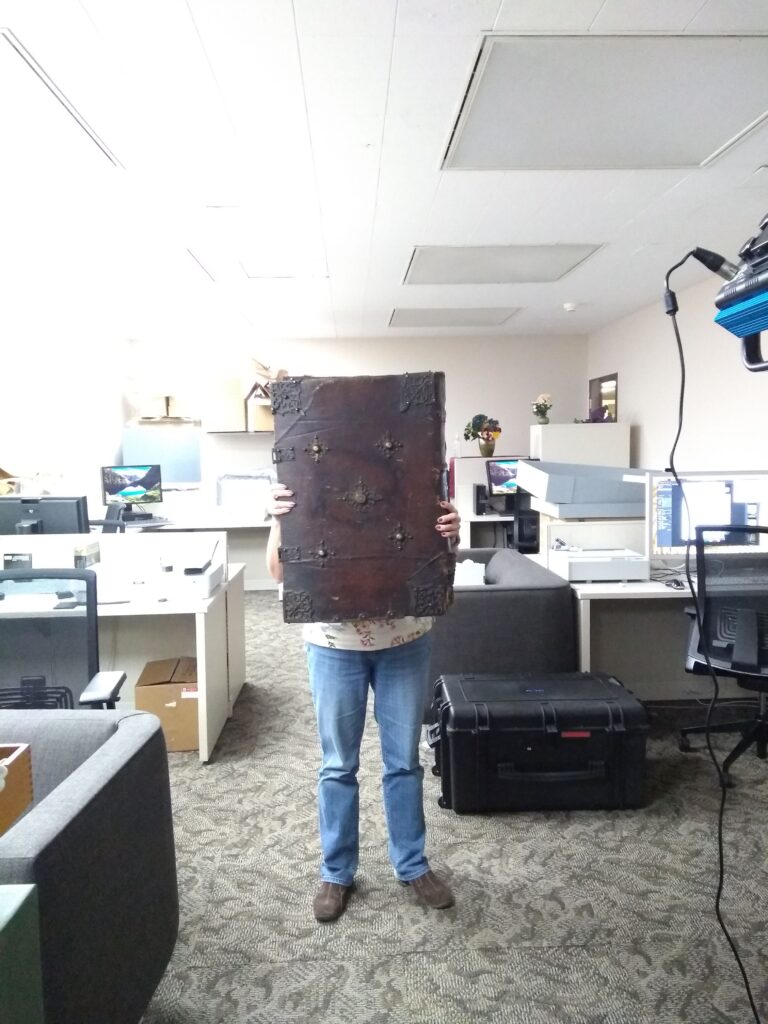

Despite best efforts to conduct condition assessments prior to digitization, differences among the partner holdings became apparent once the manuscripts arrived in Bloomington. Not all codices are the same–binding, size, fragility–and the number of leaves were either initially unknown or under-recorded. While documents are more straightforward, not all are flat (e.g., scrolls) or uniform in size (e.g., papal bulls v. binding fragments). Every item is truly unique, some requiring extra prep time before capture, all requiring careful consideration for capture. Below you can see a sample of these variations. Since we are conducting digitization on an institution-by-institution basis, the groupings of items change. While “mass digitization” principles like capture of same-type or same-size objects as part of a batch are not even a remote consideration, the variety across institutions creates a hard reset for each institutional “batch” we confront.

Not all codices are the same–binding, size, fragility–and the number of leaves were either initially unknown or under-recorded. While documents are more straightforward, not all are flat (e.g., scrolls) or uniform in size (e.g., papal bulls v. binding fragments). Every item is truly unique, some requiring extra prep time before capture, all requiring careful consideration for capture.

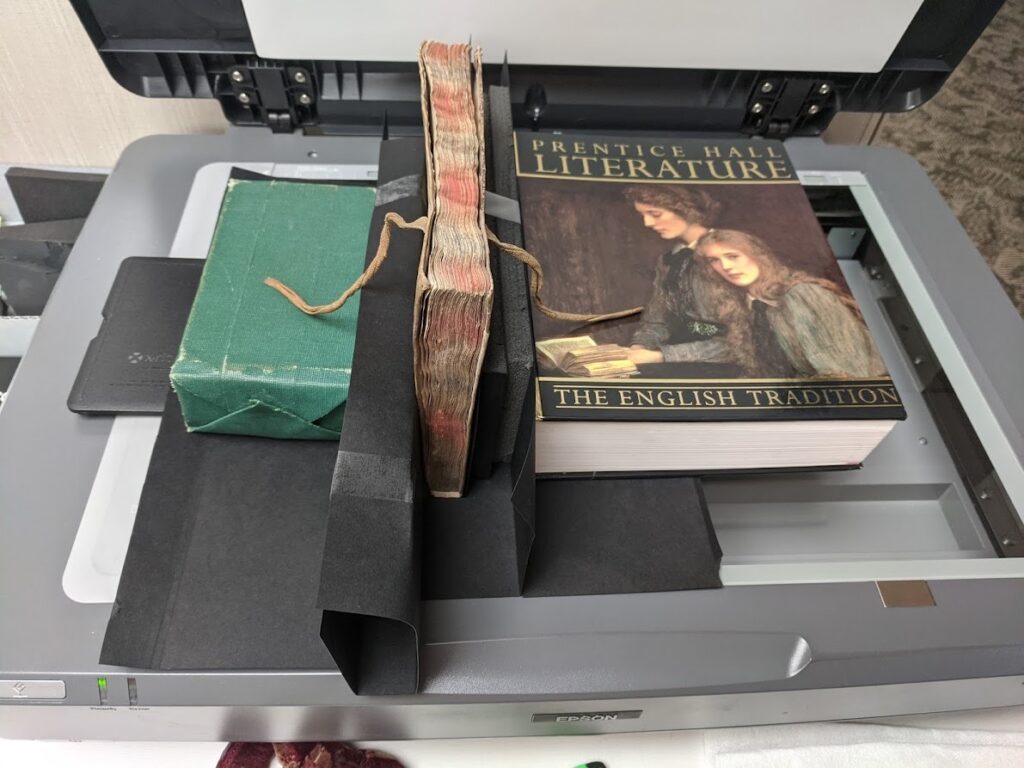

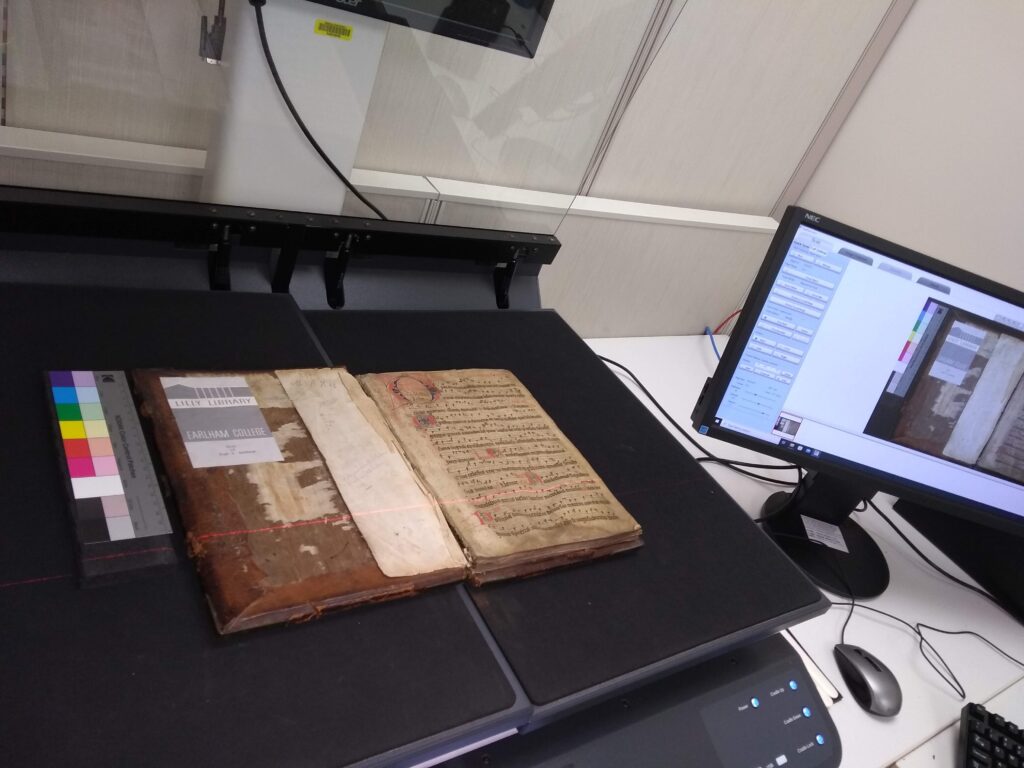

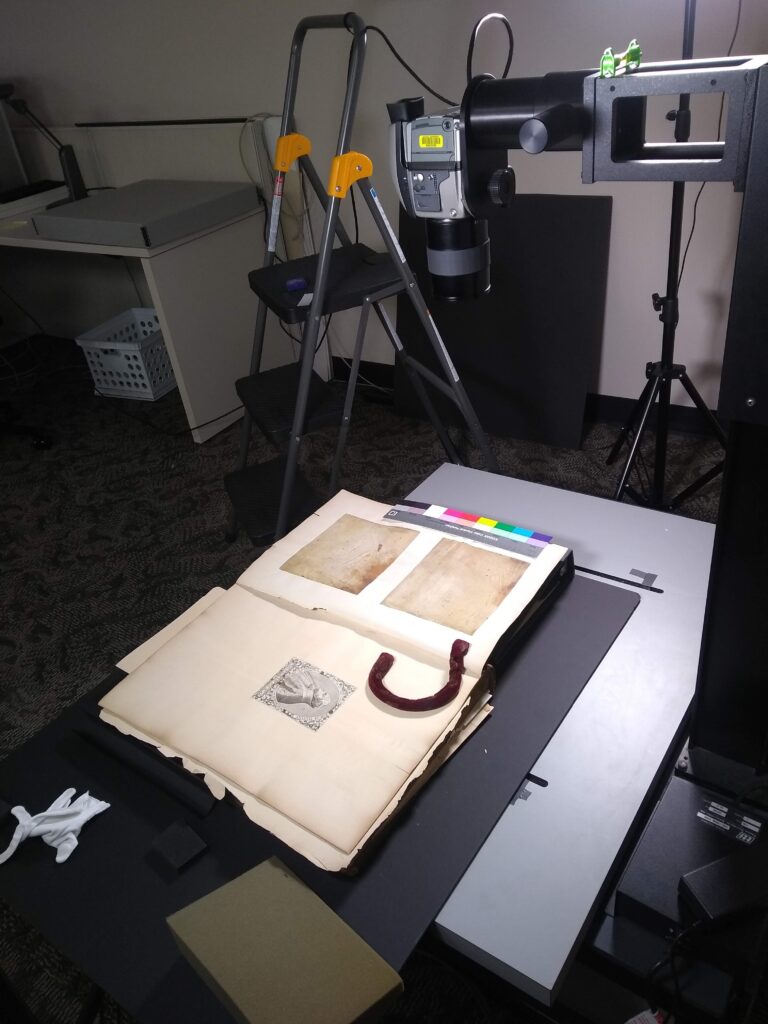

The first 6 months of capture was about trial and error. Propping materials for consistent capture with color bars, rulers, clips, and page weights entailed an equal dose of wizardry and physics. Admittedly we went into this thinking our greatest challenge would be proper capture of illuminations, but we needed to afford the same-level or even greater attention for capturing spines and edges. In those first six months we experimented with yoga mats, snake weights, bone folders, bricks wrapped in archival paper, foam cubes, foam boards, acid-free, black card stock, clips, and glass plates while balancing color bars and rulers. During the “trial and error” time period, our per-page-image cost was coming in at $4.11 an image – cost prohibitive even with our original inventory estimate. By January and February, we moved from experimentation to a more-or-less reliable rotation of effective use of the “digitization accouterments.” Our per-image cost was coming in at $1.91 an image. Between March and September, we were averaging $1.12 per page. As we re-forecast our budget to accommodate the additional items uncovered between grant submission and site visits, we will estimate costs at $2.25 image, leaving room for the unforeseeable (we still have 10 more institutions pending digitization).

Propping materials for consistent capture with color bars, rulers, clips, and page weights entailed an equal dose of wizardry and physics.

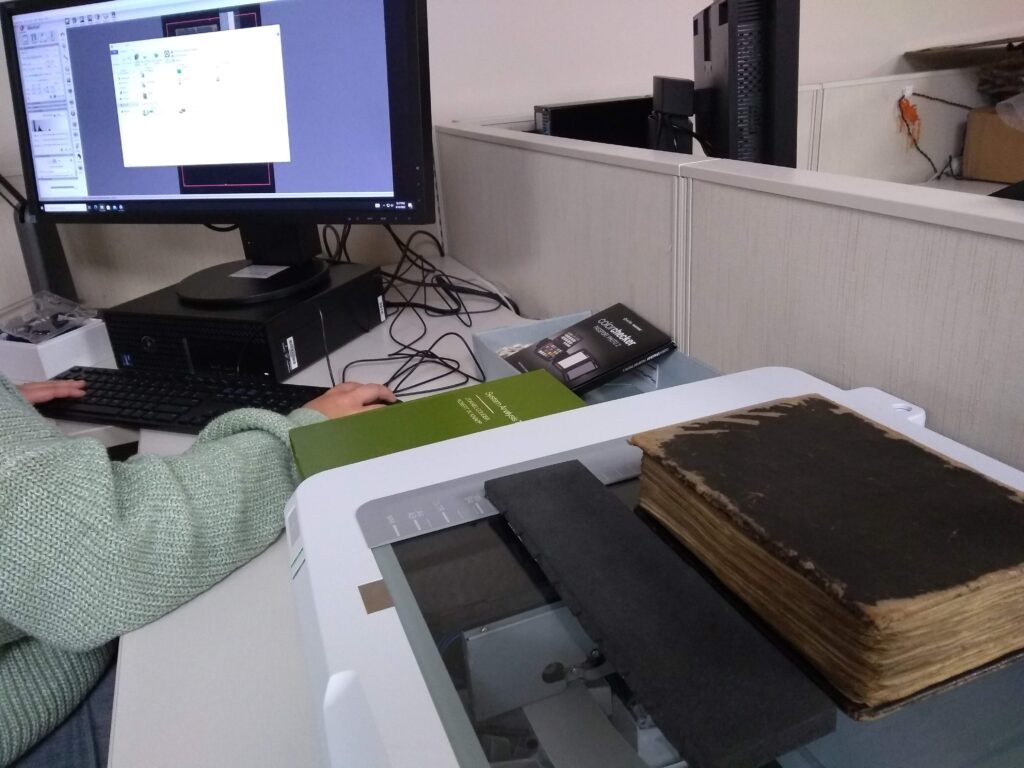

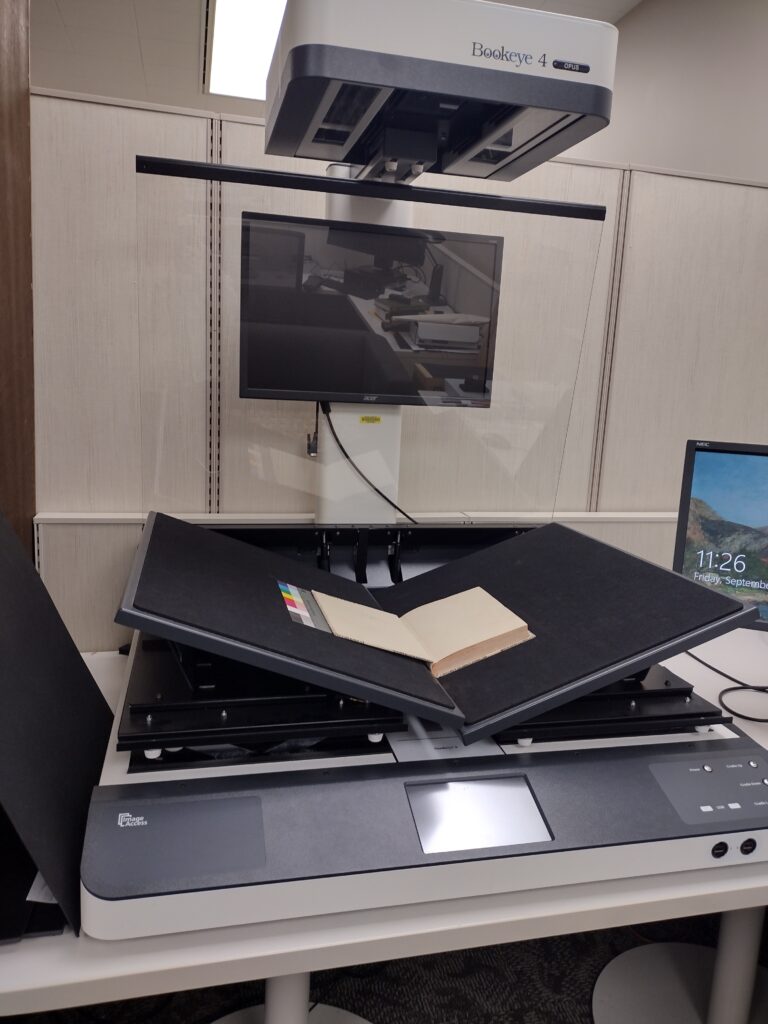

The IU Bloomington digitization team, led by Kara Alexander, Digital Media Specialist, and Caitlyn Hastings, Digital Imaging Specialist, continue to rotate through four digitization stations, depending on the materials:

- an overhead book scanner, Bookeye 4q;

- a camera stand setup with a Hasselblad H1/P45, Dracast LED lights and needed filters

- two flatbed scanners, Epson Expression 11000XL and 12000XL.

With inventorying and in-take marking the start of the digitization process, we additionally have three rounds of quality control toward the end of the process. Once items are digitized the files are run through a script that checks color profile, resolution, etc. This is what we call our “auto QC.” We then run through two rounds of visual QC — one led by the digitization team and one led by the subject experts. We inevitably have a feedback loop that requires correcting capture, but those instances are a small percentage of the total images captured.

When we plan for digitization, especially when estimating time and costs, the many steps before and after imaging need to be part of the equation. This labor is often hidden — careful handling, multiple levels of quality review, proper storage — and becomes more pronounced when working across twenty-two Midwest partner institutions. Thankfully, our partners have been instrumental in making this process as painless as possible with their endless patience, especially as we got off to a slow start due to the pandemic, and their helpful attention to detail.

Blog post inspired by a poster presentation for the Council for Library and Information Resources Digital Hidden Collections Symposium:https://osf.io/ugzkt (PDF of poster).